|

The first conversation was with my new friend, Katie. Katie is a very experienced kindergarten teacher and she's volunteering with us here at Dodge right now. She just returned from Selma, and I asked her how it went. Katie is white and she told me about the power of being the minority in the large group of activists assembled there. She was also impressed and awed by the diversity of organizations present. The people there represented a wide variety of churches, civic organizations and social movements. We talked a bit about how it feels to be the minority in one sense and to be part of a big and diverse body coalescing around one commonality. We are teachers, so, of course, the next obvious leap is how it feels for non-white students in a predominantly white classroom, and the experiences of minority families in mostly white schools. Katie told me about the struggles of a scattering of Somali folks in her own school system and how they feel isolated if they are "tokenized" and evenly distributed across classrooms in a grade level. Katie suggested that the conscious effort to cluster kids of color in classrooms in predominantly white schools seems to work out better for families and for white kids too. Why? Probably because in conversations around empathy, diversity and differences, nobody feels really good about being the sole example, the one who is "the most different." And any group of people, even if they share skin color, is truly diverse. How does a teacher reinforce this? It seems easier for young children to recognize the differences in people, to discover real empathy, across a greater number of kids. White kids, when directed to notice the diversity of, say, hair color, in a group, will notice that everyone is just a bit different. Imagine mostly white kids, and one black kid embarking on the same conversation. Initially, with little practice, they might be prone to noticing the more extreme differences in hair color. In other words, one is the loneliest number in the social setting of school. The more we notice and celebrate differences of being and differences of approach with kids, the better. But the more subtle the differences, the richer the conversation becomes and the more likely it is to trend away from generalization and assumptions about groups of folks. My conversation with Katie reminded me of the work of Louise Derman Sparks and Julie Olson Edwards. They wrote a book called, "What If All the Kids are White?" The text provides an interesting look at race and research in child development in America, and the authors present some concrete strategies for shaping and supporting anti-bias curriculum in the classroom. Dodge Nature Preschool supports an anti-bias approach in the classroom, but, in a private school with only half day programming and a self-selected population of families and kids, it really behooves us to keep revisiting how we support inquiry into differences, even when many of the kids we teach are white.

|

| Louise Derman Sparks & Julie Olson Edwards |

"Do you see any berries?"

She stomped her booted foot in the mud. "I want some now! I told you, I'm HUNGRY!"

I smiled. "But look, where are the berries?"

"Hiding from the birds."

"I'm not sure."

"Let's get some apples then."

The apple trees stand along the western fence. You can guess what they look like right now. "Are there apples on the trees? Do you see any?"

She tossed her head, stomped again and squished up her face. "But I'm hungry and I want some apples!"

Ah, the self-centerdness of the young child. All of nature shall bend to her will.

This interlude was very funny, but it underscores an important connection. Helping children build empathy, to think beyond themselves, is one of the first steps toward joining a community and the world at large. We work to help young children grow empathy all day, every day. To consider the needs and wants of other people is the first step toward considering the general fabric of existence. Turn-taking, patience, impulse control-- these are all part and parcel of building empathy for the young. And, you have to practice, because here on earth, it all works together. No apples without sunshine, rain, dirt and bees. Ultimately, honoring differences=honoring the earth. Teaching empathy and supporting anti-bias in the classroom is a very natural function of learning how to be a functioning, conscientious member of society. We are in this together. Later, when children are older, and they have had more experience with perspective-taking and understanding differing points of view and experiences, they will be ready to take the perspective of the earth and its resources, to see how we all fit together and to understand the rippling effect of existence and the marriage of human life and ecosystem.

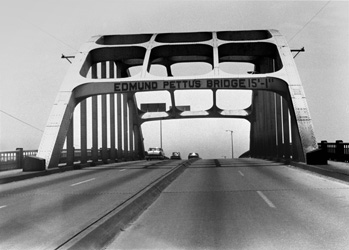

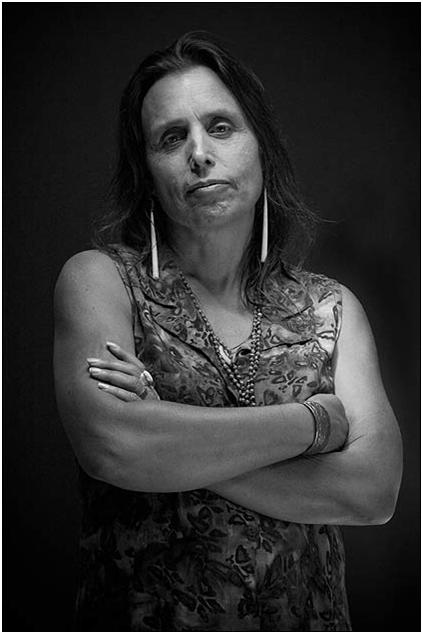

Readers of this blog know that one of my heroes is Winona LaDuke. LaDuke founded Honor the Earth and she is perhaps the foremost champion of land rights. She fights and she usually wins. She fights for our general right to an earth that is free from exploitation and pollution, and she fights for the specific rights of indigenous and minority people who often get the shaft when the land they live on is compromised or exploited by economically powerful forces. Economic power is often the legacy of a long history of majority rule by one group over another. And there we are, back to the subject of bias, where we started. I see anti-bias curriculum and empathy-building in the preschool classroom as the beginning of a lifelong conversation to mitigate imbalances of power. From Selma, to Ferguson, to Dodge, we people all have a right to a voice in this rich, complicated, civic conversation. And, it is our duty, as empathetic citizens, like the Lorax, to "speak for the trees" and to listen for those voices we sometimes have a harder time hearing.

|

| Listening to the Land: Winona LaDuke |

No comments:

Post a Comment